This book offers a music-centered approach to the contested history, memories, and identities of greater Dersim. Through laments, songs, oral history, and shifting performance contexts, it reveals how music captures violence, loss, migration, and longings for a lost, idealized past. Combining ethnography, archival research, and multi-sited fieldwork, the study uncovers fragmented traditions, hybrid styles, and the emotional worlds they express.The book is aimed at researchers of music, memory, trauma, and (Eastern) Anatolian cultures.

Alevieten vormen de grootste religieuze minderheidsgroep onder Nederlanders met wortels in Turkije. De meerderheid wordt gevormd door soennitische moslims. Bij het grote publiek is echter weinig bekend over het geloof van alevieten: het alevitisme. Wat is het alevitische beeld van God, de mens en de natuur? Hoe hebben alevieten zich door de eeuwen heen georganiseerd? Hoe ziet de geloofspraktijk van het alevitisme eruit? Aan de hand van vijfentwintig in het Nederlands vertaalde mystieke gedichten van een zestiental alevitische dichters uit de veertiende tot en met de twintigste eeuw, geeft Mahmut Erciyas middels bondige toelichtingen een antwoord op deze vragen. Daarmee krijgt de lezer een grondige inkijk in de geloofsleer- en praktijk van het alevitisme. Mahmut Erciyas (Rotterdam, 1975), is als historicus afgestudeerd aan de Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen. Sinds zijn afstuderen is hij werkzaam als adviseur in het sociaal domein bij de lokale overheid.

Das Anliegen der vorliegenden Untersuchung ist es, mit der Theorie der multiplen Differenzierung einen soziologischen Blick auf Religion und die besonderen Übersetzungsverhältnisse am Beispiel der organisations- und milieuspezifischen Lage der Aleviten in der Türkei zu werfen. Dabei werden die spezifischen Anerkennungs-, Aushandlungs- und Transformationsprozesse der alevitischen Glaubensgemeinschaft betrachtet. Elif Yıldızlı arbeitet die Spannungen im Kontext von Religion in der modernen Gesellschaft und die Paradoxien zwischen verschiedenen (religiösen) Formen und der Funktion der sozialen Integration heraus. Dafür ist die Konzeptualisierung der Differenzierung u. a. zwischen (alevitischer) Organisation und (alevitischem) Milieu notwendig. Somit trägt diese Arbeit mit einer aufwendigen theoretisch-empirischen Analyse zur (religions-) soziologischen Erforschung verschiedener Integrationsformen der Aleviten bei als Beispiel für die Ausdifferenzierung einer neuen religiösen Milieutypologie.

Media, Religion, Citizenship explores Alevi media and the ways in which it has generated a particular form of citizenship for Alevis in Turkey and across Europe. Alevis are a vibrant, transnational community across Europe whose claim for recognition has been denied. Drawing on an ethnographic study of the community, interviews with media workers, and analysis of television programmes, Emre demonstrates how Alevi media has paved the way for transversal imaginaries and rights claims that include different localities. Media, Religion, Citizenship also contributes to the decolonising of media studies by situating Alevi media within the history of Alevi movement and engaging critically with Eurocentric accounts of media and citizenship.

“Confronting the past” has become a byword for democratization. How societies and governments commemorate their violent pasts is often appraised as a litmus test of their democratization claims. Regardless of how critical such appraisals may be, they tend to share a fundamental assumption: commemoration, as a symbol of democratization, is ontologically distinct from violence. The pitfalls of this assumption have been nowhere more evident than in Turkey whose mainstream image on the world stage has rapidly descended from a regional beacon of democracy to a hotbed of violence within the space of a few recent years.

In Victims of Commemoration, Eray Çaylı draws upon extensive fieldwork he conducted in the prelude to the mid-2010s when Turkey’s global image fell from grace. This ethnography—the first of its kind—explores both activist and official commemorations at sites of state-endorsed violence in Turkey that have become the subject of campaigns for memorial museums. Reversing the methodological trajectory of existing accounts, Çayli works from the politics of urban and architectural space to grasp ethnic, religious, and ideological marginalization.

Victims of Commemoration reveals that, whether campaigns for memorial museums bear fruit or not, architecture helps communities concentrate their political work against systemic problems. Sites significant to Kurdish, Alevi, and revolutionary-leftist struggles for memory and justice prompt activists to file petitions and lawsuits, organize protests, and build new political communities. In doing so, activists not only uphold the legacy of victims but also reject the identity of a passive victimhood being imposed on them. They challenge not only the ways specific violent pasts and their victims are represented, but also the structural violence which underpins deep-seated approaches to nationhood, publicness and truth, and which itself is a source of victimhood. Victims of Commemoration complicates our tendency to presume that violence ends where commemoration begins and that architecture’s role in both is reducible to a question of symbolism.

Sufism, Politics and Community 2021

Ayfer Karakaya-Stump

Winner of the 2020 SERMEISS Book Award for outstanding scholarship in Middle Eastern/Islamic Studies. Explores the transformation of the Kizilbash from a radical religio-political movement to a religious order of closed communities.

The first comprehensive social history of the Kizilbash/Alevi communities; Combines conventional sources with newly discovered ones generated within the Kizilbash-Alevi milieu; Argues for a readjustment in focus from pre-Islamic Central Asia to the cosmopolitan Sufi milieu of the Middle East when exploring genealogies of popular Islam in Anatolia; Offers a critical assessment of the long-standing Köprülü paradigm in the field of religious and cultural history of Anatolia; Provides a new perspective on the Ottoman-Safavid conflict, and on Sunni-Shiʿi confessionalisation in the early modern period; Opens new avenues of research in the study of other ‘heterodox’ communities in the Islamic world

The Kizilbash were at once key players in and the foremost victims of the Ottoman-Safavid conflict that defined the early modern Middle East. Today referred to as Alevis, they constitute the second largest faith community in modern Turkey, with smaller pockets of related groups in the Balkans. Yet several aspects of their history remain little understood or explored. This first comprehensive socio-political history of the Kizilbash/Alevi communities uses a recently surfaced corpus of sources generated within their milieu. It offers fresh answers to many questions concerning their origins and evolution from a revolutionary movement to an inward-looking religious order.

What is the function of clerical leadership in Alevism based on sociocultural and political understandings? To answer that complex question, Deniz Cosan Eke examines the political, cultural, and religious debates surrounding Alevis and the Alevi movement in relation to the ideas and claims of the Turkish state, Alevi communities in Turkey, and migrant Alevi communities in Germany. The book, which focuses on the emergence of collective emotions in religious rituals, the struggle of religious groups in migration processes, and the leadership role of clergy in social movements, is of great interest to a wide readership.

Creating New Ways of Practising the Religion 2019 Ahmet Kerim Gültekin (Full access)

This brochure examines the transformation dynamics of social change in Kurdish Alevi communities, while mostly focusing on the increasing sociopolitical and religious role of talips.

Markus Dressler tells the story of how a number of marginalized socioreligious communities, traditionally and derogatorily referred to as Kizilbas (”Redhead”), captured the attention of the late Ottoman and early Republican Turkish nationalists and were gradually integrated into the newly formulated identity of secular Turkish nationalists.

Identity and Managing Territorial Diversity 2013

Elise Massicard

This book examines the development of identity politics amongst the Alevis in Europe and Turkey, which simultaneously provided the movement access to different resources and challenged its unity of action.

While some argue that Aleviness is a religious phenomenon, and others claim it is a cultural or a political trend, this book analyzes the various strategies of claim-making and reconstructions of Aleviness as well as responses to the movement by various Turkish and German actors. Drawing on intensive fieldwork, Elise Massicard suggests that because of activists’ many different definitions of Aleviness, the movement is in this sense an “identity movement without an identity.”

De laatste jaren is er in Nederland veel, meestal negatieve, aandacht voor de islam. Aan werkelijke kennis ontbreekt het vaak. Dat er soennieten en sjiieten bestaan is doorgaans nog wel bekend. Maar hoeveel mensen weten dat er in Nederland tussen de 80.000 en 100.000 alevieten van Turkse afkomst zijn? Dat alevieten in Nederland relatief onbekend zijn, is niet vreemd. Alevieten bidden niet in een moskee. Voor hen is geloof een privézaak, die je beleeft met vrienden en dorpsgenoten. Het alevitisme is een humanistische filosofie, waarbij de mens en humane waarden als gelijkwaardigheid tussen man en vrouw centraal staan. Al vijftig jaar zijn er Turkse alevieten in Nederland; ze hebben inmiddels een plaats in de samenleving verworven en vervullen belangrijke functies op de arbeidsmarkt. Als gevolg van de toenemende negatieve berichtgeving krijgen de alevieten steeds meer de behoefte naar buiten te treden om te vertellen wie zij zijn en welke waarde zij hechten aan hun geloof. Aanleiding voor de landelijke overkoepeling van alevitische verenigingen HAK-DER om een onderzoek op te zetten. alevieten van de eerste en tweede generatie komen in ‘Mijn Mekka is de mens’ aan het woord over hun achtergronden, cultuur en oriëntatie op de Nederlandse samenleving.

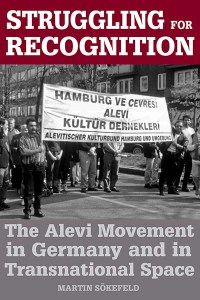

As a religious and cultural minority in Turkey, the Alevis have suffered a long history of persecution and discrimination. In the late 1980s they started a movement for the recognition of Alevi identity in both Germany and Turkey. Today, they constitute a significant segment of Germany’s Turkish immigrant population. In a departure from the current debate on identity and diaspora, Sökefeld offers a rich account of the emergence and institutionalization of the Alevi movement in Germany, giving particular attention to its politics of recognition within Germany and in a transnational context. The book deftly combines empirical findings with innovative theoretical arguments and addresses current questions of migration, diaspora, transnationalism, and identity.

In Cosmopolitan Anxieties, Ruth Mandel explores Germany’s relation to the more than two million Turkish immigrants and their descendants living within its borders. Based on her two decades of ethnographic research in Berlin, she argues that Germany’s reactions to the postwar Turkish diaspora have been charged, inconsistent, and resonant of past problematic encounters with a Jewish “other.” Mandel examines the tensions in Germany between race-based ideologies of blood and belonging on the one hand and ambitions of multicultural tolerance and cosmopolitanism on the other. She does so by juxtaposing the experiences of Turkish immigrants, Jews, and “ethnic Germans” in relation to issues including Islam, Germany’s Nazi past, and its radically altered position as a unified country in the post–Cold War era.

Mandel explains that within Germany the popular understanding of what it means to be German is often conflated with citizenship, so that a German citizen of Turkish background can never be a “real German.” This conflation of blood and citizenship was dramatically illustrated when, during the 1990s, nearly two million “ethnic Germans” from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union arrived in Germany with a legal and social status far superior to that of “Turks” who had lived in the country for decades. Mandel analyzes how representations of Turkish difference are appropriated or rejected by Turks living in Germany; how subsequent generations of Turkish immigrants are exploring new configurations of identity and citizenship through literature, film, hip-hop, and fashion; and how migrants returning to Turkey find themselves fundamentally changed by their experiences in Germany. She maintains that until difference is accepted as unproblematic, there will continue to be serious tension regarding resident foreigners, despite recurrent attempts to realize a more inclusive and “demotic” cosmopolitan vision of Germany.

Dr Ali Yaman & Dr. Aykan Erdemir (Full Access)

Alevism–Bektashism: A Brief Introduction,” authored by Dr. Ali Yaman and Dr. Aykan Erdemir, offers a clear and accessible overview of the Alevi-Bektashi tradition for a broad readership. The book outlines the historical development of Alevi and Bektashi communities across Anatolia and the Balkans, introducing key elements such as the Hacı Bektaş Veli legacy, the Four Gates–Forty Stations (dört kapı kırk makam) doctrine, and the central role of ritual practices including the cem, semah, and musahiplik. It also highlights the importance of the ocak system and the spiritual authority of dedes within the communal structure.

In addition to its historical and doctrinal focus, the book discusses the modern transformation of Alevi-Bektashi communities in the context of urbanization, secularization, and migration. It examines contemporary identity debates, institutionalization processes, and the rise of Alevi organizations in Europe. As a concise entry point into a diverse and multilayered tradition, the work serves as a valuable resource for students, researchers, and general readers seeking a reliable introduction to Alevism and Bektashism.

The Emergence of a Secular Islamic Tradition 2003

David Shankland

This volume is dedicated to the Alevis and based on sustained fieldwork in Turkey. The Alevis now have an increasingly high profile for those interested in the diverse cultures of contemporary Turkey, and in the role of Islam in the modern world. As a heterodox Islamic group, the Alevis have no established doctrine. This book reveals that as the Alevi move from rural to urban sites, they grow increasingly secular, and their religious life becomes more a guiding moral culture than a religious message to be followed literally. But the study shows that there is nothing inherently secular-proof within Islam, and that belief depends upon a range of contexts.